If Youve Had Valley Fever and Been Treated for It Can You Get It Again

The Due west is under a triple threat: the influenza, valley fever, and COVID-nineteen. Hear how patients and doctors are battling valley fever during the pandemic in a new report on Science Friday .

Arthur Charles used to first each day with a morning walk with his married woman. The loop around his neighborhood in Bakersfield, California wasn't usually hard for the 50-year-old to complete. Then 1 mean solar day, two years ago, Charles could barely reach the corner of his street. The routine walk felt like he was running a marathon.

"I couldn't breathe. I was tired," he recalls.

Arthur Charles is a resident of Bakersfield, in the southern Cardinal Valley of California. He works every bit a major league baseball recruiter and rec specialist at Westward Side Recreation and Park Commune. Credit: Kerry Klein/KVPR

Charles visited his physician, who thought he might have pneumonia, and prescribed a round of antibiotics. Charles was sent home. Subsequently that evening, he was pouring sweat, running a fever, and vomiting. Unexpected trips to urgent care connected for 3 weeks—but no one could effigy out what was wrong. One evening, his wife noticed that he was barely breathing while he dozed off. They rushed to the hospital, where Charles' oxygen levels were alarmingly low. "They said if I would have went to sleep that nighttime, I wouldn't accept woken up."

After he was admitted to the hospital, his symptoms—shortness of breath, vomiting, dizziness, and extreme exhaustion—grew worse.

"That was the commencement time I've ever felt similar I can't do anything. I but felt helpless," he says. "I've never felt and then weak so beat in my life."

Finally, after several misdiagnoses, a blood test revealed that Charles did non take a bacterial or viral infection. He had breathed in a fungus that had hijacked his lungs—and was headed for the rest of his trunk.

The doctor told Charles' family unit he might die.

Expiry By Mucus

Charles had valley fever, which he continues to boxing today. This disease, medically known as coccidioidomycosis, is caused by the fungus Coccidioides, or Cocci for curt. The unsafe fungus lingers in the soil and dust in the American W, likewise as United mexican states, and Key and Due south America. Anyone who lives, or fifty-fifty passes through, these regions has a hazard of becoming infected.

Valley fever isn't contagious. It doesn't spread from person to person similar the common cold or flu. All it takes to get valley fever is a single breath of the fungus when it'south swept upwards by the air current.

The latest numbers show that in 2018, almost 15,600 people were diagnosed with valley fever in the United States, with nearly cases coming out of southern Arizona and California's San Joaquin Valley. But these numbers but reverberate known cases reported to the Centers of Affliction Control. "That number is probably a desperate underestimate of the true number, considering people and doctors are not looking for this illness," says Orion McCotter, a old CDC epidemiologist who tracked outbreaks of valley fever.

Even though valley fever isn't well-known in other parts of the land, if you alive in endemic regions, information technology's likely that you know someone who'due south had the disease. I grew up just outside of Fresno, and have family unit living all through the Central Valley, an agriculture cradle surrounded by a fortress of periwinkle mountains. Many of my relatives have worked the fields and orchards that sprawl betwixt the valley'due south quickly-growing cities.

My mother grew up in the small town of Dinuba, and she contracted valley fever when she was a teenager. She was working her uncle's onion farm in Madera one summer, unloading bin afterward bin of the dried red bulbs. "Every fourth dimension you dumped one out, you lot could encounter all the dust flying in front of you lot. Every mean solar day nosotros'd be inhaling it, inhaling it," she tells me.

She started having coughing fits at night. She brushed it off as a common cold at first, just so her lungs began to rattle and her fever began to climb. She noticed strange ruddy-purple lumps on her legs that she confused for problems bites, and that wouldn't go away. So she became unusually tired.

"I thought, this is non my norm. I didn't know what it was."

The virtually common symptom of valley fever is exhaustion. Many people who get infected have symptoms similar to the flu—a mild cough, a low fever. Usually, these people tin can fight off the infection on their ain. They may not even realize they were ill with the fungus.

"A lot of times, when people hear about fungal diseases, they call up virtually toenail fungus and skin infections," says McCotter, now an epidemiologist for the state of Oregon. "Simply really, fungal diseases can crusade very severe infections."

The cobweb-similar shadows in this breast X-ray are signs of pulmonary fibrosis from valley fever. Since these shadows besides resemble those seen in other lung diseases, including tuberculosis or lung cancer, a chest X-ray needs to be coupled with other testing, as well equally possible tissue biopsy. The amount of scarring found in the X-ray can evidence the severity of the fungal infection. Credit: CDC/Public Domain

Approximately 40% of valley fever patients develop a pneumonia-like condition that requires medical attention. My mother was able to fully recover after doctors identified she had valley fever, just others, like Charles, may get treated for the incorrect illness. Valley fever is a commonly misdiagnosed illness because many symptoms are like to the flu and pneumonia—an consequence nosotros've also been seeing with COVID-nineteen. It can even be mistaken for lung cancer, as the mucus tin can create nodules and scarring in the tissue, which look similar to tumors in a breast X-ray.

Only in some severe cases, the fungus tin can exit the lungs and spread to other parts of the body. It tin invade the skin, bones, nervous organisation, and fifty-fifty the brain—turning into disseminated disease. Without proper antifungal treatment, the disease can last a lifetime, or even exist deadly.

For these patients, "it's either a decease sentence, or a life sentence," says Anita Sil, a microbiology and immunology professor studying fungal diseases including valley fever at the Academy of California, San Francisco. "Their lives are changed forever, and they're on antifungals forever. They don't become their normal wellness back, so the consequences are huge."

People with severe valley fever can lose their ability to work. Some lose limbs. Others lose their homes to pay medical bills. And in the most dire cases, what'south lost are their lives. These severe, disseminated cases of valley fever are rare, only well-nigh 1%. But, it is more common among immunocompromised patients, women in late stage pregnancy, and African Americans, Filipinos, and Native Americans, according to the CDC and public health departments.

The many ways the fungus can make people sick has long puzzled scientists studying the affliction. Why does the mucus cause a cough in some people, but a deadly meningitis in others?

"I've ever been interested in allowed dysfunction," says Katrina Hoyer, an immunologist and assistant professor at the Academy of California, Merced. "What is dissimilar about the immune response in the people that become astringent disease, and what is incorrect with that allowed response? Can we manipulate it?"

Researchers like Hoyer are racing to empathize the mucus better—especially as the pathogen is moving north and east. They're trying to discover how the fungus grows in the soil to ameliorate understand where valley fever may aggrandize in the future as the climate warms.

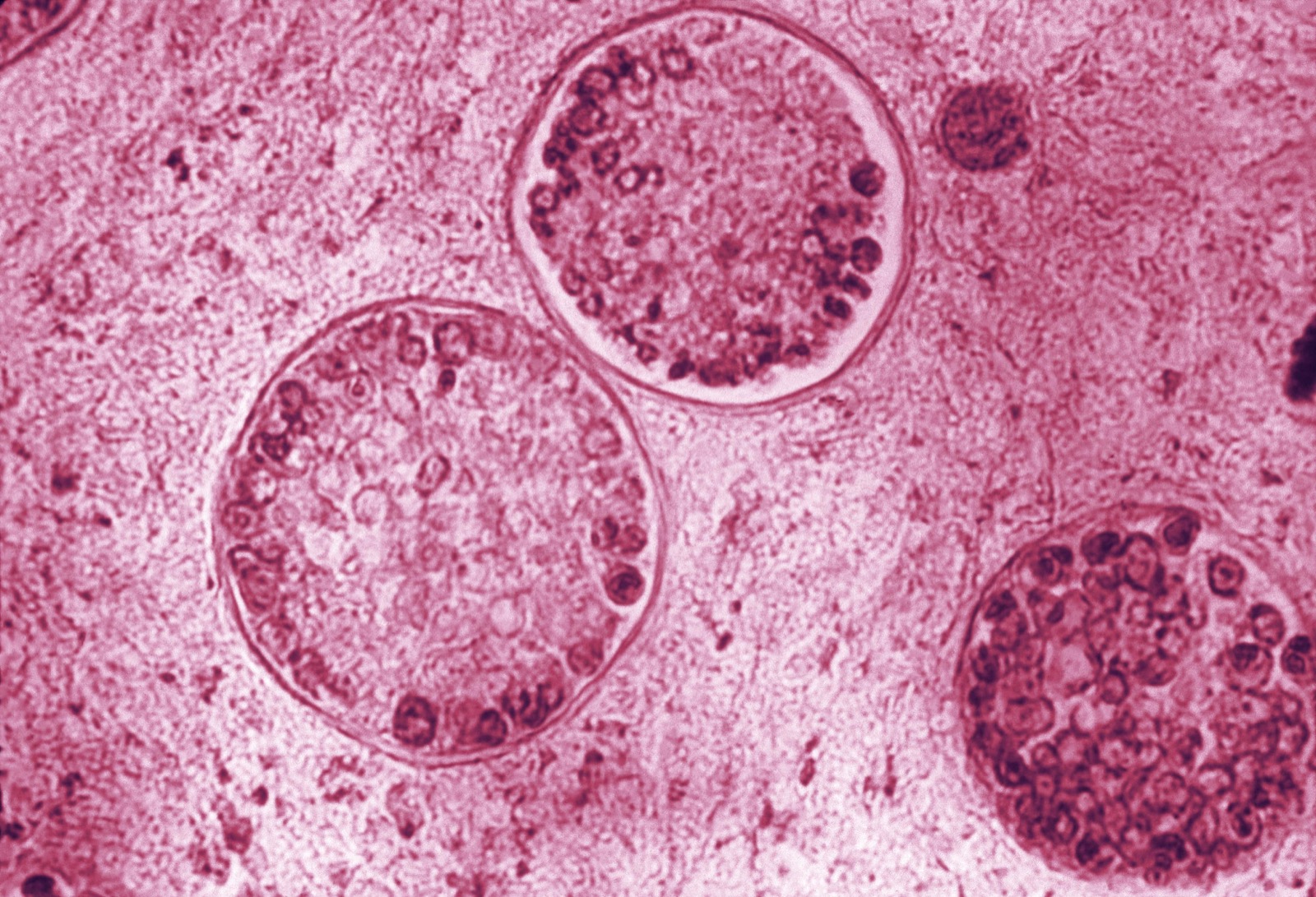

A scanning electron microscope image of the spherules of Coccidioides posadasii, one of the species of fungus that causes valley fever. The species is named after Argentinian physician Alejandro Posadas who was the get-go to place the affliction in a 33-year-old cavalryman in San Juan in 1892. Credit: Bridget Barker

The Immune System Wages War

Coccidioides is a shapeshifter: It has ane form in the soil and another in the host's lungs.

Many fungi can modify their structure under certain conditions, an ability known as dimorphism, explains Anita Sil at UCSF. Cocci belongs to a group of fungal pathogens called thermal dimorphs, which modify their cell shape in response to temperature. Once the mucus is inhaled, temperature differences between the environment and the mammalian host help trigger Cocci's transformation, Sil says.

"When they get into a mammal, they change their programme entirely, the shape of the cells changes dramatically," Sil says. Information technology morphs into a large capsule, called a spherule, that is filled with spores. These changes mean the fungus is ready to invade.

The body's immune system wages war. Normally, a diversity of allowed cells each have unlike jobs. Cells on the defensive line are watchdogs for pathogens and bespeak the warning when they enter the body. Some immune cells are like generals, in charge of directing and turning on immune responses. Others are like soldiers, battling against specific intruders. The torso's immune cells typically would engulf a bacterium or a virus to fight the infection. But these fungal spherules are big, making them difficult to swallow.

"It'south sort of similar a King Kong-type mechanism, similar you have this enormous fauna that is too big for mere mortals to conquer," Sil says.

If not stopped, the spherules can pop like an overfilled airship, unleashing more of the fungus to migrate through the body.

This photomicrograph reveals the spherules of one of the species of valley fever fungus, Coccidioides immitis. Within these spherules, you can see the spores. Credit: CDC/Public Domain

Antifungal medication is the simply treatment doctors know can quell valley fever. It works best if the disease is defenseless early. Years earlier Charles got sick, his middle son had valley fever in 2008. His doctor quickly diagnosed and treated him, tipped off past the strange lesions growing on his legs—a symptom that Charles himself did non develop. His son made a full recovery after a yr of antifungal medication.

But some people say that the antifungals are every bit bad as the disease itself, if not worse. Since the biological science of fungi is very similar to the biology of our cells, antifungal medication can likewise cause impairment while attacking the invader, says Katrina Hoyer at UC Merced. It leads to a cache of brutal side furnishings—abiding dry pare, nausea, intestinal pain. Some patients with severe valley fever receive an Four of the antifungal amphotericin B, nicknamed "amphoterrible" for causing side furnishings akin to chemotherapy.

The other problem with antifungal drugs is that they don't always destroy the mucus. They only inhibit the growth of the fungus enough for your immune organisation to try to kill it.

Despite treatment, Charles' immune system can't eradicate the fungus completely. He must keep to have antifungal medication to control its growth. He is prescribed 1 of the more common antifungal drugs, fluconazole (Diflucan). He points to a swollen crack on his lower lip, a effect of constant dry out peel and dehydration from the medication.

"I recollect I should take stock in chapstick because I use and then much of it," Charles says. "There's but so many dissimilar side effects to the medication that it'due south ridiculous. But I have to accept it if I desire to live."

"I only felt helpless. I've never felt so weak then trounce in my life."

In the worst cases, the fungus proves near impossible to control. This is what happened with Charles' older sister, Deborah.

"My sister was astonishing. She was athletic, she loved to melt and broil," Charles says. He likes to brag that he was Deborah's favorite sibling. "She would bake all my favorite desserts. She would make a matter called a sock-it-to-me block, pineapple-upside-down cake, pound cake."

Simply a few years after graduating higher, Deborah was hospitalized. She was misdiagnosed and given antibiotics multiple times before doctors concluded she had valley fever.

"When they figured it out, it was besides tardily," Charles says.

The fungus had already wreaked havoc in her body. The spores proliferated, spreading from Deborah'due south lungs, to her bones, to her spinal column, to her brain. It caused her to develop meningitis, a severe swelling of the brain's membrane. Deborah lost her eyesight. Her weight dropped from around 165 pounds to about lxx pounds.

"She lost everything," Charles says. "To watch her get from being vibrant and cute and strong every bit ever, to almost beingness an babe again was tough."

Deborah was just in her mid-twenties when she died from valley fever.

Charles' family has been hit three times past valley fever. Each case shows how dissimilar the progression of the illness can be.

The Mystery Of Misfit Immune Cells

In her lab, Hoyer is investigating differences in the immune response of valley fever patients—watching for red flags when it goes awry. She surveys anomalies in the numbers and behaviors of immune cells. In a 2018 written report with pediatricians at Valley Children's Hospital in Madera, Hoyer was able to narrow in on a specific blazon of allowed cell: regulatory T cells. "Their job is to be the brakes on the allowed system," says Hoyer.

She and her colleagues took blood samples from twenty children who were healthy, and 30 children who were infected with valley fever, and found a potential primal difference in their cell numbers. "It looks like patients that will continue to have chronic or more than persistent infection accept a higher frequency of these regulatory cells."

At UC Merced, Katrina Hoyer (pictured first), graduate pupil Anh Diep (pictured second with Hoyer), and colleagues harvest avirulent strains of the fungus. They're doing the fundamental enquiry needed to understand the immune response in astringent valley fever cases. Credit: Lauren J. Immature

More regulatory T cells could mean hitting the brakes on the immune response needed to defend the body, allowing the fungus to run amok. But Hoyer and her team are still trying to detect out what could be causing the higher levels of regulatory T cells in severe cases.

"These patients may either have more regulatory cells to begin with, or they are inappropriately developing or expanding their regulatory [cells] instead of the cells that are needed to fight the infection."

Other labs accept too looked at misbehaving T cells that fight off pathogens. For case, in 2018, clinicians at UCLA were treating a 4-yr-old boy with severe valley fever when they noticed his T cells were acting strangely. At that betoken, he was very sick with a high fever and large skin lesions on his dorsum and skull. The boy's T cell counts were normal, but they appeared to be fighting the wrong pathogen.

"If you're fighting werewolves, you demand silver bullets. Everybody knows that," says Manish Butte, the pediatrician and UCLA professor who treated the young boy. "If you hitting them with regular steel bullets, that'due south not going to piece of work."

For certain threats, you lot need specialized defenses. But if you're given the wrong message of what y'all're upwardly confronting, your assault will be ineffective. In this case, instead of gearing up to fight a fungal invader, the boy'due south T cells were armed for a battle with an allergy or a parasite, such as a worm or a tick. The cells, Butte says, had "totally the incorrect idea."

Half dozen-twelvemonth-old Abraham Gonzalez-Martinez at a checkup at UCLA in November 2019 forth with clinicians Maria Garcia-Lloret (center) and Manish Butte (left). Read and heed to Kerry Klein's feature story post-obit Abraham's treatment on KVPR Valley Public Radio. Credit: Nick Carranza/UCLA Health

Butte and his team were able to find a misstep in the messaging to the T cells: a lack of a signal poly peptide called Interferon gamma in the boy'south body. The protein is used to initiate the type of immune response needed to fight the fungus. At starting time, the doctors gave the male child a boost of the poly peptide. It helped kickstart the right immune response, but the incorrect attack response was still running, Butte says. And so side by side, the team turned to a drug typically used to treat eczema that blocks that allowed response. By giving the boy both the betoken protein and the drug, the doctors were able to steer the cells towards the right immune response—send the right message to load the correct bullets.

Over the course of about half-dozen weeks—the length of fourth dimension it typically takes for these types of therapies to kicking in—the male child'southward skin lesions melted abroad, his inflammation calmed down, and he began to recover.

"His cells were just responding," says Butte. "It was a crazy punch that his immune system needed to suddenly say, 'Oh my God, we have to fight this infection' and information technology did in simply a gangbuster sense."

The team's work is a step towards a new, constructive treatment. For now, it's just been tried in ane patient. Butte and his team at UCLA are working with Kern Medical in Bakersfield to roll out a large clinical trial. Until and so, valley fever patients however have to await for a proven cure.

But the mysteries really start long before patients demand treatment. Coccidioides survives through a journeying before it makes a home in a patient'due south lungs. What if scientists could intervene well before the war waged by your immune arrangement begins—back even before patients are exposed?

Anh Diep studies Coccidioides in the lab. Read more about the surge in valley fever inquiry at California universities on KVPR Valley Public Radio. Credit: Lauren J. Young

A Terror In The Body, A "Wimp" In The Soil

The life of the valley fever fungus, and the root of the problem, begins beneath our feet. There are currently 2 known species of Coccidioides, and both cause affliction: Coccidioides immitis, is found in California and in Washington land, and Coccidioides posadasii, which is found all over the western part of North America and parts of Central and South America. Both Cocci species tend to abound in the top layers of the earth, and like alkaline metal, salty soil—like the hard packed dirt and sandy loams that makes upwardly much of the American Southwest.

"The [valley fever] hot spots are in what we call the old Bakersfield deserts in the southwest," says Antje Lauer, a microbial ecologist at California State University, Bakersfield.

Little organic matter typically exists in this soil. Information technology's a hostile surround for many microorganisms to live in, merely this is where Coccidioides thrives. The fungus could grow in more organically rich soils if given the hazard, says Lauer, only these environments are dominated by other microbes that often outcompete Cocci.

"It's a piffling wimp," Lauer says, and adds, "That's often the case with a lot of dangerous pathogens."

Cocci may go a bursting bulbous sphere in the human body, simply it looks drastically different in the soil. During a rainy winter or monsoon season, the mucus will begin to grow in long, filamentous strands, called mycelia.

"I think it looks like fuzzy brie," says Anh Diep, a research graduate student in Hoyer's lab at UC Merced, where the squad keeps a mini-refrigerator-sized incubator filled with the fungus. Stacks of petri dishes are completely covered in puffy, cottony domes—like the fluffy stuffing that y'all'd pull out of a costly toy.

Although researchers accept been studying how Coccidioides grows in its environment since the 1930s, scientists nevertheless don't understand why information technology seems to like particular patches of clay. "I tin literally go to [i] spot year afterward twelvemonth after year, and always find the fungus at that place, but I go two meters abroad and I don't find it," says Bridget Barker, a fungal ecologist and acquaintance professor at Northern Arizona Academy in Flagstaff. "What is information technology that'southward driving that really disjunct distribution in the environment?"

Barker (correct) and her squad sample in the field. Credit: Bridget Barker

In desert regions, Barker pays attention to the plants and animals—any common factors that could influence the fungus. Recently, she found 1. Barker and her team noticed that they kept getting positive tests for Coccidioides in soil samples taken almost burrows of desert rodents, like pocket mice and kangaroo rats. These burrows might be creating perfect homes for the mucus, Barker says.

"These prissy, little microenvironments have higher humidity, lower temperature then the fungus is perhaps a footling happier," she says, and "the hair, the pare, the feces, the urine—whatever they're leaving behind in the burrow environments is a good food source."

The rodents could also potentially serve as a carrier for the illness—getting infected, dying, and decaying in the soil provides more than nutrients for the fungus to feed on, she says. Now, she is teaming up with wild fauna biologists at Arizona's Game and Fish Department to collect blood samples from rodents to see if they are infected with or have been exposed to valley fever.

Barker is not the first to brand this observation. Researchers at UC Berkeley take also found similar associations in California. Finding out what is driving the growth of the fungus in these burrows could inform people's decisions virtually what plots of soil to leave solitary. This could help lower the chances of releasing the fungus into the air.

"If we tin can understand sure times of the year, or certain areas that people are going to be more at take chances for exposure than I think we can likewise tackle the illness in that way equally well," Barker says.

The setting sun highlights a dusty haze that lingers in the San Joaquin Valley. Taken in Fresno on Nov 25, 2019. Credit: Lauren J. Young

The Demographic Dangers Of Dust

The mountain ranges of the Central Valley frequently cup a mustard brume. At dusk on a bad air 24-hour interval, y'all can see a brown soup of smog, pollution, fine particles, and dust. 1 day in November, while I was visiting family unit in Fresno, I got caught in the middle of strong winds. The dust clung to my clothing and hair. I could even taste and feel the gritty grains on my teeth. A "severe alert" notification buzzed on my phone'south atmospheric condition app: "The Valley Air District has issued an Air Quality Alert… due to blowing dust caused by windy atmospheric condition."

"Severe Alarm" in Fresno on November 25, 2019. Credit: Lauren J. Young

These alerts aren't uncommon. Canceled recess and rescheduled sports practise due to poor air quality and grit storms were the norm in my childhood. The conditions are a trigger for asthma—and prime for valley fever. On these item days, Charles and his children stay indoors. But if he must become outside, he'll put on a protective garb that many more people are wearing out today: face masks.

"We used to laugh at people who ride around in cars with the mask on or walk down the street, like 'why practise you got the mask on?' But now we're those people," says Charles. "It'south but something as uncomplicated as just a footling surgical mask, but cover yourself up and effort to foreclose from breathing in the spores, because it doesn't have much."

The mycelia of the fungus dry out out, and the sparse walls of their spores called arthroconidia easily break. These spores get carried in the air with disturbed dust, which scientists phone call "fugitive dust." Whatever disturbance to the world will do. Natural causes similar wind storms and even earthquakes have been linked to cases of valley fever. In 1977, an outbreak of 379 new cases followed a pregnant grit storm that blew through Kern Canton, while in 1994, Ventura County experienced a caseload x times its boilerplate later the Northridge earthquake stirred Cocci into the air.

Increasingly in that location are too unnatural, homo disruptions: construction of new housing, schools, buildings, solar panel fields, highways. Unpredictable, frequent bouts of fugitive dust is a growing problem in developing cities in the American Southwest, like Kern County's Bakersfield.

"People look at Bakersfield, and they remember information technology'due south just a hole in the wall, like it's only not much when you come from the big city," says Charles. But "we're growing."

The expanding southern Key Valley urban center is flanked by farms, an industry usually linked with valley fever. The very first cases documented were in agriculture workers and immigrant farmers in the 1800s. However, farmers are often wrongly blamed for the spread of the valley fever.

"Many people believe that the fungus is spread because of agricultural practices. In reality, the mucus is establish in soil that is uncultivated," says Hoyer. Agriculture fields rich in organic matter, such equally plants and fertilizer, assistance promote the microbial variety that outcompetes Coccidioides. However, when farms are abased and lie fallow, information technology provides a adventure for the mucus to return.

"We accept this a lot now in the Central Valley, that farmers are not able to farm anymore because they can't afford the h2o, especially the small-scale farmers," says Lauer. "The spores might actually germinate, and and then we have a valley fever site again." She had found this cycle happening in one of her soil testing sites at a former subcontract in the Lancaster expanse, near Bakersfield, which turned out positive for the mucus, she says.

Outdoor workers on farms and construction sites practise have a higher gamble of exposure, being out next to nearby abased fields or constantly breathing in clouds of dust from a development project.

Fresno, California. Credit: Lauren J. Young

Bakersfield, California. Credit: Lauren J. Young

"The Central Valley is this agricultural epicenter, but also this developmental epicenter," says Diep. "So when nosotros think almost the demographics that are involved most heavily in these occupations, they tend to exist Latino or Hispanic immigrants and minorities."

On peak of a socioeconomic bulwark and cultural divide, Diep says, poor access to healthcare tin filibuster proper treatment for valley fever, allowing the affliction to go more astringent: "If we remember about all the counties in California, the San Joaquin Valley has one of the lowest numbers of primary care physicians and specialty care physicians per 100,000 people in the state. And then nosotros already have a lack of these clinicians and physicians who could see patients."

Living in an endemic hot spot and working outside isn't the only danger. Some groups also accept an elevated take a chance of developing the more than severe, disseminated version of valley fever: sure racial minorities, including Filipinos, Native Americans, and African Americans—like Charles, his son, and his sis. It's a disparity that researchers say is not just acquired by higher exposure.

"Anyone who is exposed to the mucus has the same likelihood of getting infected, but some populations are more than likely to develop the more severe disseminated disease," says Hoyer.

Hoyer, Butte, and other researchers suspect information technology could be a divergence in the genes that lawmaking for the immune cells. There could be something in the immune genes that causes the body to be less constructive at mounting the correct type of immune response to fight the fungus, Hoyer says.

"Skin color, plainly, is unrelated to infection," says Butte. "It'due south the immune genes that we want to understand. And if some of these [historical reports that] African Americans are more infected is false or true, we demand to empathize why. The genetics are going to be really key."

A Growing Threat With Climate change

Better agreement the illness will exist essential, as valley fever numbers have been climbing, and show no signs of stopping.

"Our numbers are on the rise. The past 3 years, nosotros've had record years for infections," says Hoyer.

California documented over seven,500 cases of valley fever in 2018, the highest of all states. In 2018, in Kern County, valley fever numbers rose for the fourth yr in a row, according to the most recent information. Increasing rates have been seen in Arizona, Nevada, New Mexico, and Utah.

These southwest states have some of the country's fastest growing cities. As populations increase, so exercise the number of cases. Wellness clinicians may also be getting meliorate at reporting and diagnosing the illness—some states just began keeping records of valley fever in 1992.

But the fungus itself besides seems to be spreading. As hot, barren environments expand with climate change, valley fever territory could, too.

Valley fever was reported in Washington land for the first time in 2014. Soil tests came back positive for the fungus, confirming that these cases originated from within the northwest state. It surprised many researchers that the disease could be plant so far north. Information technology may soon motility even further, equally the climate becomes more favorable for the mucus beyond the United states.

"Valley fever is an example of a illness that volition probably be more widespread from climatic change," says Morgan Gorris, a postdoctoral research fellow at Los Alamos National Laboratory and a quondam graduate student at UC Irvine, who maps out environmentally influenced diseases, like valley fever. "I conceptualize we will encounter larger wellness impacts from this illness in the hereafter."

Current maps of the disease are incomplete at all-time. Valley fever is not required to be reported to the CDC. Texas, a state on the border of the endemic region, chooses non to written report valley fever cases nationally.

"Texas has been known to have cases since the 1930s," says Gorris. "Some counties practise study their case counts, just the whole state does non. It's not mandated. I feel like I would have a lot amend understanding of where the boundary of this affliction is if I had case data for Texas."

The CDC's maps are based on skin test information, a exam which revealed if y'all had been exposed to the fungus. While useful, that data was published in the 1950s, with a scattering of updates from available outbreak numbers and studies. "The population makeup was very unlike then," says Hoyer. "We also don't know exactly the endemic region anymore."

Gorris and scientists at UC Irvine created a new map to show where valley fever might expand by 2095, published in the journal GeoHealth in Baronial 2019. The map used current and future climate factors, including both temperature and rainfall. Places likely to go hot and dry, similar the endemic areas today, show upward on the map in hot pink. That hot pink reaches equally far due north and east as North Dakota—well within the midwest. Under the highest climate warming scenario, valley fever's endemic region could more than than double and the number of cases could increment by 50% by 2095.

"In the U.S., I think valley fever will be loftier up on the importance list, particularly if the endemic region expands the style our model projects it will," Gorris says.

While it may wait ominous, this map tin can help healthcare workers prepare. Public health officials can create better surveillance and disease sensation now that they can anticipate which counties and states will begin to develop cases where they may not have before, Gorris says.

"Your time to diagnosis can exist decreased, and your chances of a more than serious course of the disease decrease," she says. "Then, actually, although information technology is projected to perhaps impact more people, we want this to be used as a tool for preventing those infections, or at least mitigating the health impacts."

"Information technology'south not a disease that is restricted only to the southwest. It's something that'due south important for clinicians and the public to be aware of across the U.S."

Coccidioides isn't the simply fungal disease that may benefit from climate change, spreading beyond its original dwelling house. Some scientists propose that global warming could cause fungal pathogens to become a greater threat to humans. In that location are over v meg species of fungi. While only a few hundred of those crusade affliction, fungal pathogens are responsible for approximately ane.half-dozen 1000000 deaths every year.

"There's a lot of attention that is placed on viral diseases and bacterial diseases, but fungi are everywhere," says McCotter, who has witnessed valley fever showtime mitt in his dad and pet dogs growing up in Tucson. "I think that [fungal pathogens] are definitely under recognized."

The warmer temperatures might also change the style the fungus works in our bodies. One of the kickoff lines of defense confronting the fungus is our torso temperature. Our internal temperature helps the states kill off pathogens. It'south why we become fevers when we get sick; information technology'southward the body's way to prevent the rapid growth and spread of the pathogen, explains Hoyer.

"That poses a challenge for the fungus, and gives our allowed system a fighting chance," says Hoyer.

If the mucus adapts to the warmer temperatures, information technology'll make information technology tougher for our bodies to kill the mucus. "That reduction in that divergence in temperature [betwixt the environment and our bodies] is going to be more of a problem," she says.

Valley fever might soon be affecting many more of us. But research scientists and survivors like Charles are keeping a shut eye on its movement, spreading awareness to help mitigate the affect of the disease.

"Information technology'south non a affliction that is restricted merely to the southwest," says McCotter. "It's something that'south important for clinicians and the public to be aware of across the U.South."

"It Won't Let Go"

Arthur Charles is out on the frontlines helping others in his community understand the severity of the disease. In February in Taft, a city 45 minutes from Bakersfield, valley fever survivors and supporters stretch and warm up for a 5K run and 2K walk. Kern Medical'due south Valley Fever Plant and the Westward Side Recreation and Park Commune put on the outcome to help spread awareness of the disease—and information technology was all Charles' thought.

"I wanted to have information technology out here considering it affects and so many people," he says.

Arthur Charles helped host the showtime annual Valley Fever 5K Run and 2K Walk, with Valley Fever Institute at Kern Medical. Heed to participants and learn more about the result in an audio story on KVPR Valley Public Radio. Credit: Kerry Klein/KVPR

Charles has lived well-nigh his whole life in Bakersfield. Growing upward, he played baseball and was on his loftier school's beginning basketball team to win the country championship. He runs around Kern Canton, recruiting baseball players every bit an acquaintance scout for the Tampa Bay Rays, and works as a rec specialist for W Side Recreation and Park District.

But today, his valley fever can get out him incoherent and zapped of energy. Some days, it'due south hard to walk to his mailbox at the end of his street, permit alone make it to work. "I e'er would stay busy and practice activities, and now, I just take it one day at a fourth dimension and see what I can do," he says.

For at present, Charles continues to take his antifungal medication. Until there'due south a cure, he'll likely need them for the residuum of his life. "It won't let go of me," he says.

Only he isn't giving upwardly.

"I'm a fighter. So this is gonna be a battle, you know? If I leave, I'm gonna go out swinging and that's for sure."

Our Methods

What Inspired This Story?

The American Southwest is growing. It supports some of the fastest growing cities in the U.s.. It is filled with development projects and construction. It grapples with drought, dust storms, and drying farms. It is home to millions who are at risk of becoming infected with the fungal disease, valley fever. I became familiar with valley fever while growing upward near Fresno in the Central Valley of California. My mother had caught the fungal affliction when she was a teenager. When she told me about her experience, I was captivated: a fungus that grows in the soil and floats in the current of air could cause illness in humans.

She was able to recover after visiting the doctor, merely some aren't as lucky. I hadn't understood the harm information technology tin do to patients and their families until I began to mind to those currently struggling with valley fever, like Arthur Charles in Bakersfield, California. Science Friday also received an overwhelming response from those impacted by valley fever, with over 50 calls to the SciFri VoxPop app and dozens of listener emails. Reading and listening to each story revealed the sheer diverseness of symptoms and outcomes—fever, rash, lung scarring, seizures, lost limbs, lifetime medication, death.

Amidst these drastically different cases lies a disparity issue. Reports have shown that more severe valley fever occurs in African Americans, Filipinos, and Native Americans. Valley fever is too gaining attention nationally, equally its endemic region could expand with climate alter. The latest findings and stories are not but important in creating a meliorate picture of the disease today—but where it might be headed in a future warming climate.

your valley fever stories

Rebecca B. from N Carolina, talks near her married man:

Hullo, my proper noun is Rebecca Dark-brown, and my married man, Dusty, has valley fever. He was diagnosed in 2017 with Cocci meningitis. It disseminated to his brain, and he has had 4 or five strokes. And nosotros moved to North Carolina so his dad can aid me take care of him.

Matt from Cripple Creek, Colorado:

I had valley fever and then bad that, somewhen, I lost my correct ankle. Doctors said when they diagnosed it, I had valley fever so bad that I was going to die. And if I didn't accept this medicine, called amphotericin. I took it, went into seizure. I woke upward the next morning, but I fought valley fever for 20 years.

Guillermo N. from Saint Paul, Minnesota, talks about his mother in northwest Phoenix:

Belatedly final year, my 83-year-onetime mother showed some kind of shadow, some kind of scarring in her lungs in a CT scan. Subsequently more tests, including a biopsy, they found that what she had was a scar that resulted from valley fever. Afterward nosotros went through the test and looking more into it, many of her friends have been in the past diagnosed with valley fever. It seems to exist owned to that region.

Mary M. from Tucson, Arizona:

Xl years agone I had valley fever, and it took me more than a year to recuperate from it. Twenty years agone my all-time friend had Valley Fever, and it concluded up killing him. Five years ago, my dog got valley fever and she recovered completely in only 5 months. So I think it'south safe to assume that pretty much everybody who lives in Tucson knows someone who has been affected by valley fever.

How Did Nosotros Written report This Piece?

This project drew upon over a twelvemonth of research, interviews, field reporting, and production. Partnering with Valley Public Radio, we reported throughout the San Joaquin Valley of California. Nosotros traveled to UC Merced and Fresno in November 2019 and Taft, well-nigh Bakersfield, in February 2020. We spoke to many experts—in valley fever hot spots and across the U.S.—who contributed contextual and historical data most this disease. We conducted over fifteen interviews with immunologists, clinicians, climate scientists, soil ecologists, epidemiologists, and fungal illness experts. We spoke with several valley fever patients to understand what it is like living with this affliction, with the assistance of Kern Medical'south Valley Fever Constitute and Valley Fever Americas Foundation. We were besides able to hear from patients and family members on the SciFri VoxPop app and the Science Fri listener electronic mail.

Credit: Lauren J. Immature

Credits

This story was produced in partnership with Valley Public Radio

Written by Lauren J. Young

Sound produced by Kerry Klein and Lauren J. Young

Reported past Lauren J. Immature, with assistance from Kerry Klein

Pattern and visuals edited past Daniel Peterschmidt

Feature edited past Lois Parshley, with additional story edits by Nadja Oertelt

Audio edited by Elah Feder and Alexa Lim

Fact-checking by Robin Palmer

Special cheers to Christopher Intagliata, Christian Skotte, Brandon Echter, Ariel Zych, Luke Groskin, Jennifer Fenwick, Danielle Dana, and all of the Science Friday staff. Additional thanks to Kerry Klein, Alice Daniel, and the staff at KVPR Valley Public Radio in Fresno, California.

Thanks to Evan Lanuza and the Valley Fever Plant at Kern Medical in Bakersfield, California.

Published April 24, 2020

Beloved this story?

Then consider donating to Scientific discipline Friday, and we can brand more than great stories like this happen!

campanelliforelut.blogspot.com

Source: https://methods.sciencefriday.com/valley-fever

Belum ada Komentar untuk "If Youve Had Valley Fever and Been Treated for It Can You Get It Again"

Posting Komentar